Air logistics companies are grudgingly writing off the traditional peak season as weak macroeconomic conditions drag out the freight downturn longer than expected. Low rates will carry over into next year, even if demand eventually picks up, because many businesses are negotiating contracts to lock in low prices instead of shopping for one-time quotes when ready to ship, analysts say.

Airfreight remains mired at the bottom of a 16-month downturn and, by some measures, is worsening on the cusp of the busy season when retailers rush in orders for big shopping events and the holidays.

The soft Chinese economy, slower industrial production, a persistent inventory overhang and other factors are suppressing orders and the need for freight transportation. Air shipping demand dipped 2% in July year over year, one point more than in each of the preceding two months, according to freight intelligence provider Xeneta. During the first half, airfreight volumes fell 8.1% from the same period in 2022, the International Air Transport Association reported. The slowdown in volumes easing since early this year.

The flattening of the downward slope likely has more to do with the baseline effect from last summer, when volumes started their sharp fall, than any meaningful pickup in demand, experts say.

The reduced level of goods movement is reflected in data from BMO Capital Markets showing that flight activity for dedicated cargo aircraft declined 5.7% last month from the prior year.

“Our view of the freight cycle has worsened. I think we are seeing a lot of excess supply in various modes. And ultimately we feel that the demand environment is going to be muted for a sustained period of time,” said BMO transportation equity analyst Fadi Chamoun on a recent company podcast. In air, “there is a lot of capacity that is coming into the market. Load factors are already at a six year low … and capacity is still outgrowing demand.”

A slight improvement in U.S. consumer spending on goods in July could foreshadow a retail peak that nudges up freight demand in the fall, but with an inventory correction still underway, it is unlikely increased shopping will be realized in freight volumes. And Chamoun warned in a research note that tighter credit availability due to the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy takes more than a year to change business behavior and work its way through the economy. Decreased capital expenditures, slower payroll growth and higher unemployment are likely outcomes in the near future, which may push any airfreight market recovery until mid-2024.

Tepid demand combined with more available transportation as passenger airlines rush to restore international widebody flights continues to weigh on shipping rates. Capacity is about 7% to 9% higher than last year and 3.7% more than in 2019. The global average price for moving goods by air is more than 40% lower than a year ago, but the rate of decline leveled off four months ago.

Supply and demand pushed down average global spot rates to $2.48 per kilogram in early August.

Second-quarter earnings reflected the sharp airfreight falloff. Asian carriers reported cargo revenue fell 50% to 60%. European airlines with freighter fleets saw revenues fall between a third and a half. U.S. majors American, Delta and United said cargo sales fell 37% to 40%. Global freight forwarder Kuehne+Nagel’s operating profit for air cargo plunged 65% as low volumes combined with low rates drove down revenues by 48%. DSV and DHL Global Forwarding posted similar declines in airfreight revenue.

Spot market adjustment

After a year in which customers bought an increasing share of transportation through the spot market because rates dropped below contract rates on many trade lanes, the pendulum is swinging back. With global rates for immediate transactions flattening out, shippers and freight forwarders are changing tactics to secure longer-term contracts with rates at the low end. As previously reported, many forwarders are under pressure to reduce costs because they are overextended on capacity after renting freighter services for extended periods and are heavily discounting rates to fill their aircraft.

Average spot prices remain about 15% below contract rates, but the shift toward the cash market appears to have halted since the second quarter, according to analysis by WorldACD. However, the split varies significantly between trade corridors. On Asia-Pacific to Europe trade, spot market transactions represented 55% of the total last November but are now about 45% of the market as shippers seek the stability of contract pricing, the research firm said. The spot market share for the trans-Pacific has dropped 7.5 points since January to 67%.

U.S. freight forwarders allocated 53% of their inbound volumes in early August to the spot market, down from a peak of 56% in May, Xeneta reported.

“Going into the usually critical winter rates negotiation period, it’s clear shippers will have the upper hand. We are already seeing more shippers relaunching contract negotiations with their logistics service providers to push down airfreight rates,” said Niall van de Wouw, chief airfreight officer at Xeneta, in a monthly bulletin. “Shippers are also looking for longer, 12-month commitments to reduce their costs.”

A recent rise in jet fuel prices has kept a floor under freight rates as airlines push through fuel surcharges. But van de Wouw projected that shippers will successfully push back on surcharge adjustments because of the buyer’s market.

Has air cargo reached bottom?

“Unfortunately … there is no peak season to be expected in 2023. There are no signals either on air or sea, at least not for the time being,” Kuehne+Nagel CEO Stefan Paul said during the earnings briefing, adding that air cargo demand will likely remain stuck at current levels before picking up early next year.

Although the global economy has avoided recession and consumer confidence is relatively strong, leading indicators for airfreight are clouding the coming months.

Global industrial production is currently 6% below pre-pandemic levels because of a slowdown in China, as well as higher energy prices and uncertainty caused by the Ukraine war.

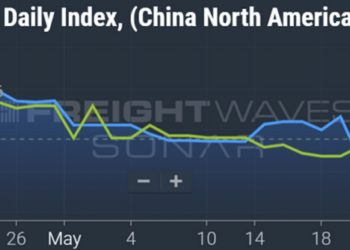

Economists have cut their growth forecasts for China, where factory activity has contracted and exports fell 14.5% in July versus 2022. Exports to the U.S. dropped 23%. Imports also fell for a ninth straight month, indicating soft domestic demand. Germany’s industrial production suffered a bigger-than-anticipated fall in June as well. Government figures show output from German factories slid 1.5% amid a stagnant economy.

Manufacturing in the U.S. has been in contraction territory for nine months.

Many retailers are still rebalancing inventory levels after a pandemic buying spree and reluctant to place new orders until the direction of consumer demand becomes clear, acting as a drag on import volumes.

The U.S. inventory-to-sales ratio increased in June to 1.41 versus 1.3 a year ago, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Apparel wholesalers like Nike, Adidas and Under Armour have the worst inventory positions, with excess stocks 40% higher than before the pandemic, said Jason Miller, professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University, during a webinar hosted by Flexport. Other sectors that need to whittle down backlogs include computer wholesalers such as Dell and HP, home improvement retailers, and furniture wholesalers. Of those sectors, apparel is the one that most often uses airfreight to deliver goods from production areas to market.

The Entertainer, the largest toy shop in the United Kingdom, is buying less because its warehouses have plenty of merchandise. “It’s not that we’re not buying from China. It’s just that we’re not buying the same volume from China because we’re wanting by the end of the year to have a lower stock level than we started the year. The best way to describe it is a correction year,” Chairman Gary Grant said on the BBC World Business Report.

Ocean shipping giant Maersk earlier this month downgraded projections for global container volumes, saying they could fall up to 4% from a previous forecast of no more than 2.5% because of tepid economic growth and signs that the inventory correction will last through year-end. Shippers are more likely to take advantage of plunging rates and an oversupply of ships to ship by ocean rather than air even if demand doesn’t pick up in the near future.

“We had expected customers to draw down inventories around the middle of the year, but so far we see no signs of that happening. It may happen at the beginning of next year,” CEO Vincent Clerc said during an earnings briefing. “Consequently, the uptick in volumes we had expected in the second half of the year has not occurred.”

Laptops illustrate the shift in mode from air to ocean. S&P Global Market Intelligence recently reported that U.S. laptop imports fell 8% year over year in the three months ending May 31, but imports by sea soared 132% while those by air fell 30%. Demand for laptops and personal computers is still relatively soft but better than expected.

Worldwide shipments of tablets, a product that typically moves by air, posted a decline of 30% year over year in the second quarter, according to preliminary data from International Data Corp.

The gap between the growth rate for air cargo and global goods trade suggests that airfreight is suffering more than container cargo from the slowdown in global trade, which was 2.4% less year over year in May.

In the U.S., Americans are expected to fully deplete savings built up during the pandemic this quarter, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco said, which could slow the economy if people spend less. The end of the student loan payment pause also means millions of people will have less disposable income for goods purchases. Meanwhile, Moody’s said credit card and auto loan delinquencies are higher than in 2019, suggesting people are burning through their savings from the past three years. The credit ratings agency said delinquencies are at 7% and could get worse next year.

The airfreight demand trajectory continues to deteriorate, according to the Bank of Montreal’s investment arm. The 12-month moving average for freighter flight activity in July contracted 4.5% year over year compared to a 4.3% decline in June. Asia led the way, with flight hours for dedicated cargo aircraft dropping 19% in July from the prior year.

“The air freight demand cycle has not bottomed yet,” BMO’s Chamoun said in a client note.

Bruce Chan, senior research analyst at Stifel, said in a monthly airfreight newsletter that the market has hit bottom, which “may be more of a flat hull than a V-shape. . . We see green shoots with consumer confidence and inflation abatement, which could swing the balance in favor of a modest peak.” Other logistics professionals are also increasingly optimistic about an uptick because of major product launches from tech companies this fall.

Chamoun said his outlook is for four to six more quarters of muted demand. And fully rebalancing supply and demand is likely to take years.

“There is maybe a good case that b2b, or consumer-type freight, has bottomed. But the b2b, or industrial manufacturing freight, is still on a downward trend. We really don’t see an inflection point in demand for freight transportation on the horizon,” Chamoun argued on the podcast.

Click here for more FreightWaves/American Shipper stories by Eric Kulisch.

Sign up for the weekly American Shipper Air newsletter here.

RELATED READING:

Lufthansa Cargo profits fall nearly 100% on weak shipping demand

Cargo downturn hurts Asian carriers more than global competitors

Price war keeps air cargo rates below natural level

The post Wait for airfreight recovery could extend deep into 2024 appeared first on FreightWaves.