With the doors open at FreightWaves headquarters in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to outside visitors who wanted to witness in person the August State of Freight webinar with CEO and founder Craig Fuller — the first time for that — a market Fuller called the most “opaque” he had ever witnessed was the focus Thursday.

July was a month in which a trucking company that had been around for almost 100 years imploded. But the collapse of Yellow, unlike its role in the July webinar, was a relatively minor part of this month’s discussion. (July’s State of Freight webinar also featured extensive discussion about a possible strike at UPS (NYSE: UPS), which did not occur).

Instead, the August chat between Fuller and FreightWaves Director of Market Intelligence Zach Strickland, sponsored by Prologis (NYSE: PLD), kicked off by focusing on some bullish data that came at an odd time of the year.

It was a hot July for more than the weather …

Freight volumes generally decline or are flat in July, Fuller said. “We’ve got this anomalous environment with the tender volumes,” he said, citing the Outbound Tender Volume Index in SONAR. And outside of July 2020, which was another anomaly as the economy climbed back from the depths of the pandemic, OTVI never increases in July. But it did this year.

“If you go back historically, July is a pretty soft market,” Fuller said. He cited as reasons some usual factors — people take vacation around July Fourth — but others that might be less obvious, like the fact that July is a time when auto manufacturers close down some manufacturing lines as they retool for a new model year. Back-to-school merchandise, Fuller said, “has already moved into the distribution centers, so it is really a month where most people take off.”

But OTVI did not react normally this year, Fuller said, “and it’s telling us something is different about this freight economy.” OTVI exited June at 10,670.78; it finished up July at 11,211.4.

One possible reason for the recent strength in OTVI: the impact of federal infrastructure spending making its way into the economy more than a year after the Biden administration’s legislation was signed. “It takes awhile for governments to allocate these funds,” Fuller said. “I think what we’re seeing is the very early stages of some of that money moving through.”

But carriers are not benefiting from rising volumes

The flip side of OTVI is the Outbound Tender Reject Index, which measures freight tenders offered by shippers or brokers that are rejected as they make their way through routing guides. At its tightest, OTRI exceeded 28% on several days in late 2020 and early 2021. At its lowest, it sank to around 2.5% in May. More recently, it was standing at 3.5% to 3.6%.

The increase in OTVI while OTRI lingers at low levels, Fuller said, due to “the amount of capacity that was added during the COVID economy,” a figure he put at 25%. “That means you have a lot of excess capacity that we have to burn through. That needs to happen.”

And it is occuring, Fuller said, citing comments from industry executives who have seen companies enter bankruptcy. “But the problem is the market simply cannot correct fast enough to give anyone any sense of promise about the second half,” he added.

Fuller looked back on the weak freight market of 2019 that was highlighted by the collapse of New England Motor Freight in February 2019 and Celadon at the end of the year. He described those shutdowns as “bookends” to that freight market. And if history repeats itself, Fuller said, the closure of less-than-truckload carrier Yellow might be “the start of the great purge.”

The great inventory purge may be over

Strickland said the inventory situation that is impacting freight markets is one in which “we’re still adjusting to this world after COVID.” That period was marked by “this bubble where everybody went out and bought a bunch of stuff.” But that was followed by “this narrative about inventory reduction, Target and Walmart; they all had to get their inventories under control.” Data is showing that inventories have drawn at a rate faster than anytime since 2016, Strickland said.

Fuller said planning in the supply chain often goes out as much as a year, which means that beginning around May and June 2022, freight markets were signaling a significant downturn in demand. Inventories were “probably carried longer than retailers would have normally.” But if that planning signaled inventory purge starting in June 2022, “it means we’ve gone through a period of at least 12 months where they’ve liquidated inventories, and it’s quite possible that the market is now catching up to that reality.” That could be a factor in the rise in OTVI, Fuller and Strickland agreed.

Rates probably won’t go lower, but they’re not rising either

Trucking rates are measured in SONAR through several indices, but the National Truckload Index (Linehaul Only) is considered the most significant because it does not include fuel costs. The NTIL.USA, for the entire country, has risen and fallen between $1.50- and $1.75-per-mile rates in the past three months.

“I think what it is communicating is that there is a bottom in the market and rates will not go much lower,” Fuller said. Carriers have made a “rational decision that if they lower rates any further, they cannot survive. The market is communicating that this is the low end of the rate target.”

Contract rates are not falling as rapidly as might be expected, Fuller said. “And I think what’s happening is that a lot of carriers have rationalized that they don’t want to lower their rates in their RFP too much,” he said, even though as a result, freight is moving into the spot market. “I think the fear is that if they lock in low contract rates, they’re stuck with them.”

Fuller described the whole picture as “the most opaque market I’ve ever seen.”

Container rates unlikely to ever get back to pandemic levels

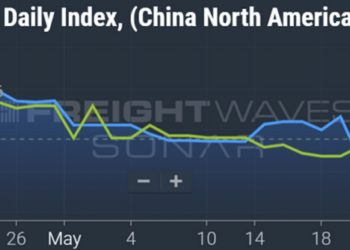

The Freightos Baltic Index for China to the North American west coast, FBXD.CNAW in SONAR, hit a peak in September 2021 at about 20,586. More recently, it has fallen to about 1,815.

Similar to how Fuller saw the current rise in OTVI linked to U.S. government infrastructure spending, that wild rise in ocean freight rates was also tied to COVID-related stimulus, he said.

But Fuller added that “nearshoring,” the gradual process to move manufacturing away from China and back to North America, is also playing a role in his conclusion that the global economy is not likely to ever return to those sorts of maritime rates. Short of a major military conflict, Fuller said, “I can’t see a scenario where our container rates get to the levels where it was during COVID.”

More articles by John Kingston

Louisiana staged accident scam investigation springs back to life with 5 new indictments

How one city is curbing overweight trucks

Analysts weigh in on new C.H. Robinson CEO’s first earnings call

The post Takeaways from State of Freight: A surprising volume increase in July appeared first on FreightWaves.