As the global trade recession began to materialize in 2022, there was a great deal of hype over the potential boost to ocean container demand once the Chinese government ended its COVID restrictions and lockdown measures. But now that hype has faded and what was once hoped to be a great reopening and much-needed boost to volumes is looking more and more like a great flop.

The Inbound Ocean TEUs Volume Index – USA is derived from bookings data and shows the total ocean container volume departing all global origins bound for U.S. ports based on the vessel departure date. Chart: FreightWaves SONAR. To learn more about FreightWaves SONAR, click here.

In the chart above, the Inbound Ocean TEU Volume Index from China to the U.S. provides a seasonality view that compares 2023 volumes thus far (white line) with volumes over the past four years. It was late March/early April of 2022 (green line) when the Chinese government announced another round of COVID restrictions and lockdowns. This new round of lockdowns at first appeared as if they would make the transportation of goods to and from major manufacturing hubs nearly impossible. That caused some to automatically (and haphazardly) assume the following scenario: The lockdowns would cause a backlog of goods and pent-up demand that would eventually cause another container surge similar to what occurred after the first round of lockdowns in 2020. But we were able to see a different story playing out in real time through our bookings data.

Port of Shanghai, China to the U.S. – Booking Volume Index (red), vs. Port of Ningbo, China to the U.S. – Booking Volume Index (yellow). Chart: FreightWaves SONAR Container Atlas.

Those who were expecting an impending freight surge hadn’t realized that, even though access to the Port of Shanghai was largely blocked due to landside restrictions (i.e., road closures), shippers were able to reroute volumes through the closest alternate major port in nearby Ningbo. As the chart above clearly displays, the resulting decline in Shanghai bookings and container volumes was more than offset by a surge of volumes through Ningbo during that time (from the rerouted Shanghai bookings).

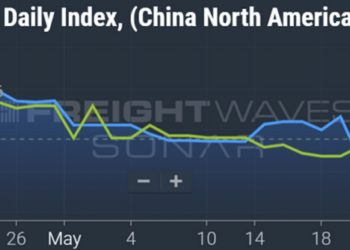

The Inbound Ocean TEUs Volume Index – China to USA is derived from bookings data and shows the total ocean container volume departing Chinese ports bound for U.S. ports based on the vessel departure date. Chart: FreightWaves SONAR. To learn more about FreightWaves SONAR, click here.

As the year progressed into the second half, global container volumes began plummeting, and there were still no signs of a surge in volumes coming out of China. As the hopes of a potential freight wave eventually began to fade, it was still widely believed that China’s reopening would (at least) be a major factor in helping boost volumes and possibly create a “soft landing” for the global ocean container market. Unfortunately, that boost in volumes never appeared. Instead, volumes continued to soften out of China during a largely nonexistent peak season. The weakening volumes were then met by emerging headwinds such as the inventory glut, weakening consumer demand and increasingly negative economic landscape.

Chart represents U.S. Customs reported China to U.S. maritime import shipment volumes. Chart: FreightWaves SONAR. To learn more about FreightWaves SONAR, click here.

That trend has continued through Q1 of 2023, and now, it is becoming increasingly clear that hopes of a reopening container boost are all but gone. While April saw China’s share of U.S. imports bounce back up 6% month over month to 37% (chart above), this small bump in volumes is not likely to become a sustained trend, and there are now a growing number of signals flashing red within Chinese government-reported economic data as well as commodity markets. The following signals should be heeded as a warning that the road ahead could get worse for China.

Currently, the inventory destocking phase (and when it will be complete) is one of the most important challenges facing China to U.S. container demand and was discussed at length by the CEO and CFO of Maersk in the ocean carrier’s most recent earnings call. To better understand the phases of the inventory replenishment cycle, we can examine average container volume (in twenty-foot equivalent units) per booking from China to the U.S. The chart above displays the monthly average of TEUs per booking from January 2022 through today. This has been a key indicator of the various stages of the replenishment cycle — and was a critical component of why import demand was dripping off a cliff in mid-2022. In looking at this ratio, we were able to see that importers (i.e., Samsung) were cutting purchase order quantities in a way they thought would result in largely the same number of bookings, just less overall TEU volume per booking. The signal for a new replenishment cycle for U.S. importers will be for this ratio to move back above an average of two TEUs per booking. Currently it resides at its lowest reading since early 2019 at 1.7 TEUs per booking.

The Inbound Ocean TEUs Volume Index vs. the Inbound Ocean Shipment Index – China to USA. Both indices are derived from bookings data, and together, highlight how the total container volumes per shipment can help understand the replenishment cycle. Chart: FreightWaves SONAR.

With the volume per booking being at its lowest level since COVID began, it’s no surprise that our latest ocean container bookings data for the U.S.-bound container volumes departing China continue to exhibit the overall weakness in U.S. import demand, with any chances of a second-half rebound getting increasingly unlikely. This weakness in booking volumes was again echoed in the latest April contraction of the Caixin China General Manufacturing PMI, which fell unexpectedly to a four-month low of 49.2 in April (and below the midway point of 50 that delineates expansion and contraction). New orders fell to 48.8 from 53.6 and buying activity contracted to 48.8 from 53.6, with Chinese firms reporting that delivery times had improved as vendors were less busy.

Source: Jeffrey Snider, Eurodollar University

Macroeconomist Jeffrey Snider with Eurodollar University has been following the China economic data closely, and in a recent update he covered the chart above highlighting the tight correlation between the World Bank’s Pink Sheet Base Metals Index Data and the China Producer Price Index stating, “The worse it gets for China’s factories (because no one in America or Europe is buying anymore), the more prices are going to fall, beginning with commodities. China’s Producer Price Index and factory gate prices both accelerated to the downside in April, meaning even more deflation is on the way (and that’s not a good thing). Prices of materials going into China’s factories are falling and prices of stuff coming out are going down just as fast.”

The Ocean Booking Volume Index – All Global Ports to China is derived from bookings data and shows the total ocean container volume booked from all global ports bound for Chinese ports based on the date the booking was accepted/confirmed by the ocean carrier. Chart: FreightWaves SONAR.

Imports to China also unexpectedly shrank by 7.9% year over year (y/y) to $205.2 billion in April, missing market expectations amid weak consumer demand, lower commodity prices and a stronger dollar. In the chart above we can clearly see the declines in container volumes from all global ports destined for Chinese ports, with the index dropping over 20% (on a moving seven-day average) since the beginning of March 2023.

Source: Jeffrey Snider, Eurodollar University

Crude oil imports were down 1.45% y/y to the lowest level since January, purchases of copper fell 12.5% and purchases of iron ore fell 5.1%. Chinese imports from ASEAN countries fell 6.3% and from the U.S. fell by 3.1%. As we can see in the chart above, Snider again points out the high correlation between Chinese imports and the World Bank’s index tracking commodity prices. Chinese manufacturing is an enormous source of demand for raw materials, so it is largely no surprise that it has such a tight correlation with commodity prices worldwide.

Source: Barchart.com WTI Crude Oil Futures: June 2023 – blue; July ’23 – green; August ’23 – orange; and September ’23 – magenta.

Meanwhile, the recent announcements of OPEC+ production cuts (along with resulting futures price action) serves as further evidence that the Chinese rebound and reopening is not materializing into the surge in oil demand that would be a primary input into an increase in manufacturing and production within China’s industrial sector and would also be a key input into a major surge in Chinese consumer demand within the services sector. The chart above represents the next four months of WTI crude oil futures, which all saw further declines on Friday, again confirming that the market is watching the balance of supply against the increasing demand headwinds and economic concerns facing both China and the U.S.

It is now becoming increasingly clear that the China reopening is not likely to cause a surge in container volumes anytime soon. These key economic indicators for Chinese manufacturing do not paint a pretty picture for the ocean container market in the second half of 2023 and are especially concerning for U.S. containerized import volumes.

The post Reality of ocean container volume far cry from China reopening hype appeared first on FreightWaves.