The air cargo industry underwent a serious stress test in 2023 as collapsing market demand and rates dragged down revenues, forcing many all-cargo carriers to scale back operations, postpone aircraft investments and tighten budgets, before a late resurgence in volumes lifted offered hope for a better 2024.

The course correction from 2021, when airfreight business skyrocketed to record highs as businesses looked for ways to overcome broken supply chains during the pandemic, began in early 2022 and didn’t stabilize until the fall. Airfreight wasn’t a priority for retailers because they had built up too much inventory on the misguided notion that online purchases would continue to explode while the reintroduction of more passenger flights saturated the market with belly capacity.

Many of the year’s main developments in air cargo were colored by the severe drop in profit margins, with some industry stakeholders withstanding the squeeze better than others.

Here’s a look at how the year unfolded for the air cargo sector.

Freight recession cuts deep

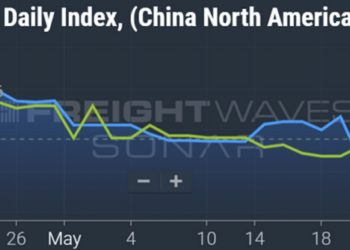

Air cargo was no exception to the recession that gripped the freight transportation sector for nearly 18 months. The industry entered the year on the heels of high-single and double-digit declines in monthly cargo volumes, but the gap gradually improved until hitting bottom in August. Since then, air cargo volumes have improved as the peak season proved better than expected, largely due to a surge in e-commerce orders for fast fashion and electronics produced in China.

Improved performance is partially related to very weak comparisons in late 2022, when demand plunged.

Freight rates were down 40% to 50% for much of the year, before rallying in recent months. Rates are now 50% ahead of 2019 levels after narrowing to about 20%.

Publicly listed airlines saw cargo revenues slide between 25% and 60%, with carriers in Asia feeling the biggest reductions. Lufthansa Cargo reported it had no profit in the third quarter compared to $352 million the prior year.

Questions remain about whether the peak-season bounce was temporary. Most experts think the market won’t really begin to recover from the prolonged downturn until the second half of 2024 because of mixed economic conditions. But geopolitical events are a wild card that could propel, or constrain, growth in the coming year. The recent diversion of container vessels around Africa to avoid the risk of missile and drone attacks could present a major opportunity for airlines and freighter operators if businesses convert some shipments to air transport to avoid delivery delays.

Plugging financial leaks

Airlines and freight forwarders responded to the dilution in revenues by taking steps to rein in costs. Many carriers canceled or postponed purchases or leases of new freighters that they planned for when the market was booming.

Air Canada reversed course on an order for two production Boeing 777 cargo jets and Cargojet scrapped plans to convert four 777s into freighters. Air Transport Services Group has paused sending Boeing 767s to repair shops for conversion and said several customers have backed out of commitments to lease freighter aircraft. Amerijet has parked one freighter and deferred major maintenance on two more in addition to eliminating some accounting jobs and closing a small logistics business.

Defections from three major customers contributed to the financial woes at Western Global Airlines, which declared bankruptcy last summer. The company restructured and was released from court protection early this month.

The weak market also impacted the big express carriers, which have cut back on flight activity. FedEx continued a multibillion dollar campaign to eliminate structural costs and consolidate operations for improved efficiency. The effort includes the Express business taking out $700 million in annual costs by reducing reliance on the hub-and-spoke network, consolidating routes and leaning more on contract carriers, commercial airlift and trucking. FedEx now has more pilots than it needs and is encouraging some of them to take jobs with a regional passenger airline.

FedEx (NYSE: FDX) and UPS (NYSE: UPS) are accelerating the retirement of older aircraft and have temporarily parked others until the market picks up. UPS offered buyouts to nearly 200 senior pilots to save money.

Freight forwarders ranging from Flexport to Kuehne+Nagel, DSV and C.H. Robinson eliminated thousands of jobs in response to slower air and ocean volumes.

Fleet freeze

Aerospace companies that specialize in converting passenger planes to freighters are expected to crank out a record number of units this year, but deteriorating international freight and e-commerce volumes chilled orders for new and aftermarket aircraft.

Many airlines and lessors are sticking with aircraft commitments to take advantage of forecast growth in e-commerce and international trade, and to modernize their fleets. But new orders have been few and far between this year — both for production freighters and cargo conversions of used passenger jets.

Most concerns about freighter oversupply focus on standard-size jets like the 737-800 and the Airbus A321. The number of conversions for small, standard-size jets exploded during the past three years to unprecedented levels.

A handful of airlines countered the trend and placed orders, or expanded their current fleets. Cathay Pacific and Turkish Airlines each ordered several copies of the new Airbus A350 freighter, which is still in the final design and certification stage. Japan Airlines relaunched its first freighter fleet in 13 years by taking three of its 767 passenger aircraft and sending them out for overhaul so they can carry large cargo containers. The first aircraft was recently delivered and will begin intra-Asia service in February for DHL Express. Spanish cargo airline Swiftair said it will lease two Airbus A321 freighters next year. Meanwhile, U.S. startup GlobalX has ambitious plans for cargo after adding its first three freighters this year.

Changes at the top

How some companies handled those outside economic forces led to leadership changes.

Air Transport Services Group (NASDAQ: ATSG), which owns cargo airlines and ground handling companies in addition to being the world’s largest lessor of freighter aircraft, fired CEO Rich Corrado over continued capital expenditures on aircraft while the airfreight market was in a hole and disappointing performance in the company’s stock. Amerijet ousted Tim Strauss as CEO when his three-year contract ended.

Freight forwarder Flexport had a messy breakup with CEO Dave Clark, less than a year after arriving from Amazon, over the direction of the company and heavy losses. The company laid off more than a third of its workforce during the year.

Other leadership transitions were planned. Atlas Air promoted Michael Steen to CEO after John Dietrich retired and then went to FedEx to become its CFO. Atlas Air also hired Martin Drew, formerly the cargo chief at Etihad Airways, as chief strategy and transformation officer. Ajay Virmani of Cargojet announced that he will step down as CEO in January and be replaced by two top lieutenants in a co-leadership arrangement.

Paying pilots

It was a busy year for labor contracts in the airline and air cargo sectors. The threat of disruption loomed over some carriers as unions flexed their muscles to influence negotiations and new deals significantly raised operating costs.

Pilot unions were able to take advantage of favorable economic conditions — a tight labor market, high inflation, crew shortages at mainline carriers as they tried to rebuild after pandemic-driven layoffs and a training backlog for new hires — to get better pay and work schedules.

A number of major passenger airlines reached collective bargaining agreements with cockpit crews. Delta Air Lines pilots finalized a contract that includes a 34% raise over four years. In September, pilots at United Airlines approved a new contract that raised pay up to 40%. American Airlines pilots also received a big raise. And Hawaiian Airlines pilots, including those hired to fly the company’s first freighters for Amazon, reached a deal that raised pay up to 33%.

Southwest Airlines pilots struck a tentative deal this month after earlier giving union leaders leeway to call a strike. Strikes are rare in aviation, in part because of federal law that severely restricts the ability of unions or management to shut down operations for leverage.

Miami-based cargo operator Amerijet agreed last summer to raise pilot pay at least 45% in a three-year deal with the union. The pay hike came against the backdrop of sharply lower revenues because of weak market conditions and cost cuts to make ends meet.

Last month, pilots at cargo airline Air Transport International laid the groundwork for union leaders to call a strike when legally allowed. The company is one of the main transportation providers for Amazon Air and DHL Express in the U.S.

Pilots at Western Global Airlines unionized in 2021 and were seeking their first contract when the carrier filed for bankruptcy protection in August. The company exited the bankruptcy process earlier this month after disposing the bulk of its liabilities.

In July, pilots at FedEx Express voted to reject a proposed deal between management and union negotiators. The deal would have raised pay by 30% over five years. Pilots had authorized union leadership to initiate a strike vote before union negotiators reached agreement May 30 on a new deal.

Pilots who voted against the FedEx deal complained about weaker job protections, back pay and alternative pension options and said pay increases were below those achieved by pilots at Delta, United and American.

Meanwhile, 1,100 ramp workers at DHL Express’ Cincinnati air hub went on strike on Dec. 7, with the impact spreading as Teamsters members at other U.S. locations honored the picket line and refused to report for work. An agreement between the two sides was reached 12 days later.

Secondary airports

2023 saw continued interest from freight forwarders in smaller, less congested airports that are able to quickly carry out cargo transfers and lower cost. Kuehne+Nagel opened an air terminal for a chartered freighter at Birmingham Shuttlesworth Airport in Alabama, while DSV began dedicated freighter flights to Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport instead of the big Phoenix Sky Harbor Airport. Maersk Air Cargo is testing a route from Bournemouth Airport outside London.

Hawaiian and Amazon

Hawaiian Airlines in October began flying cargo within Amazon’s air logistics network, an unconventional partnership that could have significant implications for both companies and competitors. It will receive more A330-300 converted freighters, provided by Amazon, in 2024 and eventually operate 10 freighters for the e-commerce giant. The partnership got more intriguing early this month when Alaska Air announced a deal to acquire Hawaiian Airlines for $1.9 billion.

Click here for more FreightWaves/American Shipper stories by Eric Kulisch.

RECOMMENDED READING:

Air cargo market: From ‘doom mongering’ to stability

Orders for freighter aircraft slow ‘to a trickle’

The post Air cargo industry faced stress test in 2023 appeared first on FreightWaves.