In early 2020, a well-known transportation executive was asked by an investor in digital freight broker Convoy Inc. to determine if its model could be sustained in good and not-so-good markets. The executive, who requested anonymity to speak candidly, evaluated the company and came away skeptical about its prospects.

The executive approached Dan Lewis, Convoy’s co-founder and CEO, with a suggestion: First, hive off a few million dollars in capital to establish some type of an operation in Chicago, the epicenter of brokerage and more than 2,000 miles from Convoy’s Seattle headquarters. Then, hire 10 or so “badass brokers,” supervised by the executive, who knew how to move freight. Once the brokerage operation succeeded, the technology would be leveraged to support the brokers’ efforts and make them more productive.

Read more: Death from overfunding: An obituary for Convoy

According to the executive, Lewis said he would take the suggestion under advisement. But the sense was that Convoy, which about five years into its existence had already raised many hundreds of millions of dollars and was very much on a roll, believed that it had built a better mousetrap based on sophisticated technology that could supplant traditional brokers. The executive’s suggestions essentially fell on deaf ears.

A person close to Lewis said that he had multiple conversations every quarter with freight executives who proposed ideas or approaches. A dialogue like that one may have occurred, the person said.

The purported decision to prioritize technology in a business so reliant on people to cover loads and deal with exceptions is poignant in the wake of the past week’s events. In a downfall unprecedented in transportation and logistics history, the one-time FreightTech darling went from a valuation of approximately $3.8 billion in the first quarter of 2022 to out of business in a little more than 18 months. Most of its remaining employees were laid off last Thursday. None received severance.

The company would pay health benefits through the end of October, at which time the affected employees could go on COBRA. This was a stark reflection of how bare Convoy’s cash cupboard had become and raised questions about its inability to conserve sufficient cash as a buffer should the freight business turn down, as it has been known to do.

Convoy’s collapse took with it funds from some of the smarter guys in the room, namely Microsoft Corp. founder Bill Gates, Amazon.com Inc. founder Jeff Bezos, mutual fund titan T. Rowe Price and investment firm Baillie Gifford. Convoy had secured $250 million in lines of credit from Hercules Capital and JPMorgan Chase & Co. It also raised money from musical legend Bono, the front man for the group U2. In all, Convoy raised about $920 million.

Convoy said it would retain some employees to attempt to sell its driver app and its back-end auctioneering algorithms that kept freight moving nationwide with a minimum of human intervention. Over the years, Convoy built software for owner-operators and small fleet dispatchers, and transportation management system portals for its customers, to bring as much of the transaction on-platform as possible so that it could be automated.

FreightWaves reported late last week that the technology had attracted two potential unnamed bidders. Before Convoy’s collapse, Amazon.com Inc., Danish maritime and logistics firm Maersk and C.H. Robinson Worldwide Inc. had kicked its tires, according to industry sources. Talks with Robinson to buy the entire company reached an advanced stage before they fell apart, sources said.

A two-pronged story

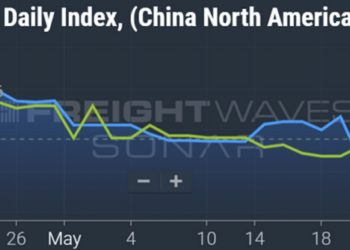

Convoy’s shutdown is a two-pronged story. The macroenvironment, which is affecting nearly every broker, clearly played a role. Freight demand and rates have pancaked since the high-octane days of 2020 and 2021. A load that could command $300 in net revenue during the pandemic and post-pandemic periods is likely to fetch half that today. That puts intense pressure on broker margins if their costs don’t get reduced and the debt they took on remains on the books.

The 18-month surge in the cost of capital was another broad-based factor. Convoy came of age in a low interest rate environment. Many businesses were venture funded because the bar for returns was as low as the rates themselves. Once the cost of money became far more dear, venture funds faced a higher bar to clear. They began demanding profits from their businesses instead of just growth alone. In a climate of soft demand and prices, many companies were unable to comply and were deemed uninvestable.

“One of the lessons learned from this is that the cost of capital does matter,” said the industry executive, who said the dramatic increase in borrowing costs was the first crack in Convoy’s bursting dam.

But there were issues that were more Convoy-centric. Co-founders Lewis and Grant Goodale were technology-focused executives. Neither had trucking or freight experience other than Lewis’ stint at consultancy Oliver Wyman from 2004 to 2007. With steadfast faith in the company’s disruptive abilities, they may have lost sight of the fact that advanced technology would not guarantee any loads, much less profitable ones, in a competitive market filled with brokers who knew how to solve freight-oriented problems. The “build it and they will come” mindset, in the end, did not succeed, especially with as many as 16,000 brokers — the approximate high-water mark attained during the pandemic — plying their trade as well, also with support from technology

Convoy had trouble divining its costs and pricing its services profitably, according to sources. Shippers were supportive of a model that could lower their costs. But it didn’t do Convoy’s margins any favors. According to the executive, Convoy broke even or at best eked out small profits even when rates were relatively high. Once rates went into free fall, Convoy was in trouble, according to the executive.

Convoy executives hoped to offset the per-load losses with higher volume in an effort to scale the business. That approach of lowering prices to buy market share works in the less-than-truckload segment of trucking because LTL is a network business that thrives on density, according to two executives. However, it does not work well in a point-to-point business like truckload, which is greatly fragmented and where density is harder to achieve.

Convoy’s model was initially based on building density in critical lanes. Then in late 2019 it pivoted to more of a focus on improving its profitability. The pandemic delayed those efforts. But by late 2020 and into 2021 it had reduced its operating expenses by 50%, according to a person close to the company.

Convoy’s load-matching technology was geared as much toward owner-operators as it was small or micro fleets. This is unlike other brokerages that focused on micro fleets. Owner-operators are generally not great candidates for backhaul loads because they are lone wolves who drive here, there and everywhere. Small fleets, by contrast, operate inside of networks with locations where they return to regularly. The focus on owner-operators left Convoy out of a potentially large chunk of load generation.

Another factor was the profile of Convoy’s shipper base. Huge brands with big spends were frequent users of the platform. However, they often had payment terms stretching out 90 to as long as 120 days, whereas Convoy had to pay carriers within a matter of days after the loads were delivered. The receivables squeeze put a hit on Convoy’s cash flow, according to the executive.

C. Thomas Barnes, a longtime transport executive who today is an investor in transport logistics companies, said Convoy failed because it didn’t have enough people with insider know-how to counterbalance the new ideas that typify an outsider’s mentality.

“Is there a need for technology? Hell yes!” Barnes said. At the same time, it is vitally important to have traditional problem-solvers on the inside to make everything work, he said.

Convoy’s failure is a microcosm of a larger problem, Barnes said. Many good, outsider ideas go by the board because the insiders’ capabilities are either not there or because a balance between the two mindsets hasn’t been struck, he said.

The source close to Convoy disputes that claim, noting that three of the first five top hires came from the freight business. Convoy also hired salespeople and brokers from the industry, especially when it had a carrier sales team, the person said. The false narrative of Convoy not having freight talent was put forth to deter people from doing business with the company, the person said.

Never got there

In the end, Convoy wasn’t big enough, nor did its efforts bear fruit fast enough, to offset the very weak market and the absence of help from the venture funding space, according to the person. The company simply ran out of time, the person said.

Convoy’s demise sparked an outpouring of postmortems on social media. All lamented the human fallout of hundreds of lost jobs. Others thanked Convoy for raising the awareness of technology’s importance in advancing the legacy brokerage business.

“You pushed us to see technology differently,” Lars Ward, vice president of business development at digital logistics startup FreightVana, posted on LinkedIn last week. “The need for better freight tech is huge and Convoy was chasing a vision” to better connect freight to carriers.

Convoy’s advancements “challenged other brokers to respond” with their own innovations, Ward wrote.

Matt Silver, a longtime FreightTech executive and investor, echoed those sentiments, writing on the same platform that Convoy’s legacy — which likely won’t come to fruition today — is that it created an “intense competition amongst the rest of the top freight brokerages” to improve their IT value propositions.

Silver lauded Convoy’s driver app, which he said “brought a ton of capacity online that was previously offline” and is a reason why the industry has “some sense of capacity availability today.”

The post Convoy’s tech focus may have obscured importance of human element appeared first on FreightWaves.